In India, the Constitution is a living document which guarantees every citizen a bundle of rights which have been described under Part-III of the Constitution. It is the most important segment of the Constitution where certain rights, like equality, freedom to express and other connected rights have been guaranteed against any arbitrary state action. The definition of state has been defined under Article 12 of the Constitution, which reads as under:

Article 12. Definition – In this part, unless the context otherwise requires, “the State” includes the Government and Parliament of India and the Government and the Legislature of each of the States and all local or other authorities within the territory of India or under the control of the Government of India.

In a nutshell, it means that any action done by the state functionaries which fall under the definition of state under Article 12, which is in contravention of the fundamental rights, can be challenged before the Court of law. It is pertinent to mention that State, does not include the judiciary, however, in the exercise of non-judicial functions of the court will fall within the definition of the State (State of Punjab vs. Ajaib Singh, 1953 AIR 10).

Right to Shelter vis-a-viz Rule of Wheels over law

In India, majority of the population resides in the rural areas and a shelter over their head has been their own responsibility, but to protect that shelter – the state has a positive duty. The recent trends reflect that right to shelter has been continuously vandalised either by bulldozers or in the name of anti-encroachment drives conducted by various municipal authorities or government bodies.

Since the 1980s, the Supreme Court has interpreted the right to life under Article 21 to recognise and include the right to housing/shelter. In doing so, the courts have placed reliance on Directive Principles of State Police, International Law and a comparative analysis across various courts across the globe.

In the past decade, there have been increasing instances of demolitions across the country. Although, demolition is not something unjust but if it is done with the intention of giving someone a punishment without hearing them or it is an outcome of some bias then it becomes unjust and arbitrary. The right to shelter guarantees does not mean a mere right to a roof over one’s head but right to all the infrastructure necessary to enable them to live and develop as a human being. A report suggests that within two years, around 1,50,000 homes were razed, 7,38,000 were left homeless across the country. These demolitions frequently violate the settled principles of natural justice, primarily the right to be heard.

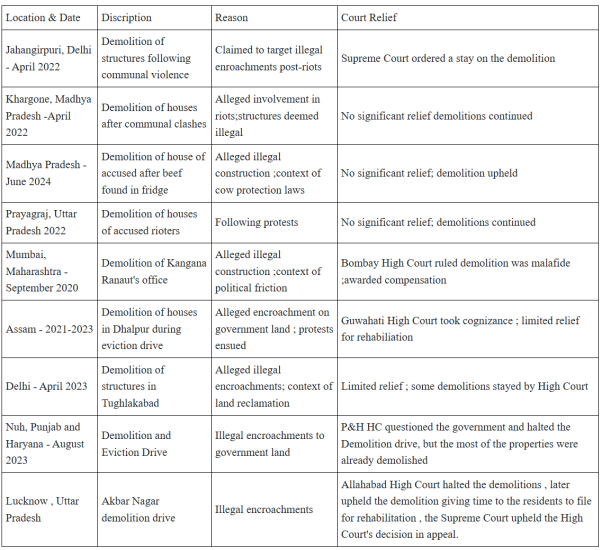

While reflecting some of these demolitions, I did a piece for Outlook India, where an overview of these demolitions was discussed. For convenience of the viewers, I am reproducing the table here which was published in the abovementioned article.

In a recent judgment titled as “In Re: Directions in the matter of demolition of structures”, the Supreme Court issued a set of guidelines to tackle the rise of arbitrary demolitions across the country. Initially, the Supreme Court took suo motu cognizance and halted various demolitions across the country and remarked that the chilling sight of a bulldozer demolishing a building, when authorities have failed to follow the basic principles of natural justice and have acted without adhering to the principle of due process, reminds one of a lawless state of affairs, where “might was right”

While issuing a set of directions to curb “bulldozer actions”, the division bench comprising of Justices BR Gavai and KV Vishwanathan held that demolishing the houses of persons on the ground of their alleged involvement in crimes would amount to inflicting a “collective punishment” on the family, which is impermissible under the Constitutional scheme.

“Right to life is a fundamental right. As already discussed herein above, with the expanded scope of law, the right to shelter has also been considered as one of the facets of Article 21 of the Constitution. In one structure, various people or maybe even a few families could reside. The question that is required to be considered is, as to whether if only one of the residents of such a structure is an accused or convicted in a crime, could the authorities be permitted to demolish the entire structure thereby removing the shelter from the heads of the persons who are not directly or indirectly related with the commission of crime.”

It is pertinent to highlight the fact that the Supreme Court acknowledged that if demolition of a house is permitted wherein number of persons of a family or a few families reside only on the ground that one person residing in such a house is either an accused or convicted in the crime, it will amount to inflicting a collective punishment on the entire family or the families residing in such structure.

“In our considered view, our constitutional scheme and the criminal jurisprudence would never permit the same.” The court held

The Supreme Court came down heavily on collective demolitions, however, inadvertently created a potential loophole in para 91. It reads: “At the outset, we clarify that these directions will not be applicable if there is an unauthorised structure in any public place such as road, street, footpath, abutting railway line or any river body or water bodies and also to cases where there is an order for demolition made by a Court of law.” By explicitly excluding “unauthorised structures” from the scope of the guidelines, the court has provided a broad and subjective category that can be misused to justify demolitions without due process or consideration of individual circumstances.

In my recent article for Indian Express, I have argued that how the term “unauthorised structures” is inherently vague and open to interpretation. Municipal authorities, often under political or administrative pressure, misuse this provision to label properties as “unauthorised” arbitrarily, even in cases where there are disputes over ownership, pending legal challenges, or extenuating circumstances. This could lead to a wave of demolitions that disproportionately affect marginalised communities, who may lack the resources to challenge such actions legally. There is also no logical reason as to why the requirements of notice and proportionality should not apply to such individuals who are residing at such “unauthorised” places.

Judicial Response and right to shelter

In the judgments of Chameli Singh vs. State of Uttar Pradesh and Shantistar Builders v. Narayan Khimalal Totame, the Supreme Court expanded the meaning of right to shelter and categorically observed as follows:

“Shelter for a human being, therefore, is not a mere protection of his life and limb. It is home where he has opportunities to grow physically, mentally, intellectually and spiritually. Right to shelter, therefore, includes adequate living space, safe and decent structure, clean and decent surroundings, sufficient light, pure air and water, electricity, sanitation and other civic amenities like roads etc. so as to have easy access to his daily avocation.”

In the judgment of Munish Ram v. Delhi Admn, the Court held that no one, including the true owner, has a right to dispossess the trespasser by force if the trespasser is in settled possession of the land and, in such a case, unless the lessee is evicted in the due course of law, he is entitled to defend his possession even against the rightful owner. Further, in the judgment of Krishna Ram Mahale v. Shobha Venkat Rao, the Supreme again retaliated, and held that where a person is in settled possession of property, even on the assumption that he has no right to remain on the property, he cannot be dispossessed by the owner of the property except by recourse to law.

The Delhi High Court in Ajay Maken and Ors v. Union of India held that the right to housing is a bundle of rights not limited to a bare shelter over one’s head. It includes the right to livelihood, right to health, right to education and right to food, including right to clean drinking water, sewerage and transport facilities. In Sudama Singh, the Delhi High Court held that prior to carrying out an eviction, it was the duty of the state to conduct a survey of all persons who may be evicted, to check their eligibility under existing schemes for rehabilitation, and to carry out a rehabilitation exercise ‘in consultation with each one of them [persons at risk of an eviction] in a meaningful manner.’

With regard to the due procedure, the Supreme Court in Olga Tellis v. Bombay Municipal Corporation, held that notice and hearing must be ordinarily provided to ensure that the procedure for removal of encroachments depriving people of their right to life constituted a ‘just, fair and reasonable’ procedure. At present the courts have focussed on the requirement to provide notice, but not so much on the requirement to carry out a hearing with residents facing evictions. A hearing prior to evictions is as much of a constitutional requirement as a notice, as held by a Constitution Bench of the Supreme Court in Olga Tellis case.

In the judgment of Suresh Tirkey v The Governor with Connected Matters, the Karnataka High Court significantly held that the right to shelter is a fundamental right of every citizen under the Constitution and any infraction of this right by State action must invite judicial intervention to protect the occupants of a dwelling house.

A conclusive note

While the right to shelter is enshrined as a fundamental right under Article 21 of the Constitution, guaranteeing the right to life and personal liberty, its practical implementation has often been undermined. Despite the Supreme Court’s commendable efforts in issuing guidelines to protect this right and explicitly acknowledging that demolitions often amount to collective punishment, significant gaps remain. Para 91 of the Court’s judgment, which excludes unauthorized structures from protection, inadvertently leaves vulnerable populations, particularly in rural areas, at risk. These areas often house the poorest segments of society, who rely on such structures for survival. This exclusion highlights the ongoing tension between legal frameworks and the lived realities of marginalized communities, underscoring the need for a more inclusive interpretation of the right to shelter.

The right to shelter is not merely a basic human need but a cornerstone of dignity, security, and equality. As one of the most vital rights under Part III of the Constitution, it ensures that every individual has a safe space to thrive, free from the fear of displacement or homelessness. Without adequate shelter, other fundamental rights—such as the right to health, education, and livelihood—become inaccessible. Recognizing and safeguarding this right is essential for fostering social justice and upholding the constitutional promise of equality and dignity for all. It is imperative that the judiciary, legislature, and executive work collaboratively to bridge the gap between policy and practice, ensuring that the right to shelter is not just a theoretical ideal but a tangible reality for every citizen.

Leave a Reply